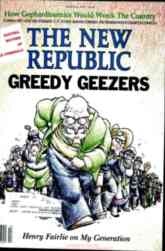

Under the headline “Greedy Geezers,” the cover of the March 28, 1988 issue of the New Republic shows a phalanx of angry over 65ers surging forward, toting golf clubs and fishing rods. The accompanying article by Henry Fairlie, 64 at the time, excoriated over 65ers as being out for themselves and ready to bankrupt the country by their demands for more Medicare and Social Security benefits. But an important recent report – Re-Designing Medicare – from the Center for Healthcare Decisions, puts the lie to the “Greedy Geezer” accusation, at least as it applies to the Californians who participated in the study.

The researchers asked almost 800 participants, 40% of whom were over 65, to consider re-designing the benefit package for current and future Medicare members Using CHAT, a computer-based simulation program, participants were given 100 “chits” to choose among 130 possibilities. The simulation forces trade-offs, and the three-hour group sessions asked participants to voice the reasons and principles underlying the choices they made.

Here are the five most frequently endorsed increases in Medicare coverage:

- Long-term care. 77% supported at least one year of coverage in a nursing home, supportive housing, or a person’s home

- Dental, vision, and hearing. 85% supported modest coverage in all three areas as new benefits.

- Mental Health. 69% wanted to provide treatment to those with less severe mental health problems, by increasing coverage from short-term to long-term with a lower co-insurance than Medicare currently requires.

- Transportation. 81% supported coverage to and from medical appointments for those who are unable to drive or use public transportation.

- Medicare longevity. 85% were willing to reduce Medicare spending on current and future beneficiaries to assure that the program would last at least another 50 years.

Since MedCHAT requires acknowledging that there is no free lunch, increases in Medicare coverage had to be paid for with Medicare savings. The five most endorsed forms of savings were:

- In place of the freedom of choice in traditional Medicare, 82% supported the use of defined networks, but most required that referral outside the network would be covered with approval of the primary care provider.

- For patients with chronic conditions like diabetes or heart failure, 88% would require patients to pay at least half of the cost for treatments that yielded tiny benefit or were more expensive than equivalent treatments.

- For those with terminal illnesses, 65% supported coverage for hospice care and palliative care, but not for treatments unlikely to make a meaningful difference. Virtually all eliminated ICU care for dying patients.

- To control chronic conditions like obesity and high blood pressure, 84% favored using incentives, with 48% endorsing penalties and rewards and 36% penalties only.

- 79% thought that high income seniors should pay higher premiums for Part B (outpatient, home health, durable medical equipment, and preventive services).

While over 65ers were less likely than younger participants to endorse many of the new limits, what stands out is how many were willing to do this. Thus while 93% of those under 40 accepted the idea of network limitations, 75% of the over 65ers also did. Interestingly, for sudden devastating illnesses or injuries, 65% of participants under 40 would continue full coverage for “long shot” interventions, while only half of the over 40 population would do so. Overall, while there were differences among age cohorts as well as among ethnic and economic groups,there was no statistically significant difference between the old and the young in devoting “chits” to ensuring Medicare’s future.

The Re-Designing Medicare project was an exercise in deliberation, not a survey. A substantial number of participants changed their views over the course of the three hour process. There was a 28% shift towards believing that Medicare should be changed in significant ways, and similar changes with regard to reducing coverage for low value treatments. There was no support for the “Greedy Geezer” hypothesis. Over 65ers were almost as open to changing Medicare as under 65ers were.

Participants were very positive about the MedCHAT process. Fifty-one percent reported understanding “a lot more,” and only 5% reported that they had learned nothing new. 44% reported that “this will make a difference in the way I consider Medicare,” and only 2% thought it was a waste of time.

Sadly, it’s not realistic to hope that we’ll have an educative political process to foster this kind of deliberation about the future of Medicare any time soon. But if the deliberative discussions embodied in the Center for Healthcare Decisions project were repeated in other sections of the country, we’d have the start of a national citizen-level voice for thoughtful changes in Medicare. If politicians begin to understand that substantial numbers of over 65ers are prepared to accept new limitations on low value care in order to support changes that make Medicare a more “health improving” and less purely “medical” program, they may be less paralyzed by fear of being attacked by an army of “Greedy Geezers.”

(See here for a PowerPoint presentation of the project, and here for a video of a panel discussion sponsored by the American Enterprise Institute.)

Jim Sabin, M.D., 75, is an organizer of Over 65, a professor of population medicine and psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, and a Fellow of the Hastings Center.

Comments

2 responses to “Re-Designing Medicare”